“When our rivers run dry and our crops cease to grow.

When our summers grow longer, and winters won’t snow.”

Rise Against, "Collapse (Post-America)"

We’ve slapped many labels on the impacts of industrial civilization on the global ecosystem. Climate change. Anthropogenic global warming. Human induced climate change. Climate destabilization. All accurate, all semantic. For all the snark about how Earth’s climate always changes and the human impacts won’t matter in the long run, Rise Against pointed out problem #1 with climate change when they wrote ‘our crops cease to grow’. If you don’t care one bit about rising sea levels flooding the homes of millions, or the mass extinction that very well could follow a few degreeS rise in global temperatures over the coming centuries, take a moment to think about where your next meal will come from. More on that later.

As with the post about resource depletion last week, I'm not going to rehash the supposed controversy about the underlying science of climate change. People with PhD’s, doing decades of research in the field, have done the hard work, and we should listen to what they have to say. This isn’t to say I dogmatically accept whatever the climate scientists have to say. As I will go over in a bit, there’s a leak one area where the observed outcomes appear to be playing out differently from how the climate models said they would. That said, I don’t accept what PR firms paid millions by fossil fuel companies have to say about the underlying causes or impacts of climate change.

|

| I'm sure those PR firms are honest actors... |

If you're interested in reading specific US projections, the National Climate Assessment is a good place to start. Yeah, yeah, yeah, I know. "I don't trust the government." Okay. Fine. Your tax dollars still paid for the NCA, so you might as well look at what you bought.

If you're not at least superficially familiar with the topic, let me bring you up to speed. Since about 1850, human beings have been burning fossil fuels at rates that have dumped more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that the biosphere can absorb. Due to the chemical properties of one carbon bonded to two oxygens, that carbon dioxide is a potent heat trapping gas. Technically, the carbon and the oxygen are double-bonded, which means the molecule traps energy better than the other gases in our atmosphere except methane. We've known this since the late 19th century. Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius identified CO2 as the principal heat-trapping gas in the atmosphere, though he did say, in 1896, that calculating how fast temperatures would rise wasn’t feasible at that time. Since then, we’ve done a lot of work documenting the rise in CO2 levels in the atmosphere, and we’ve observed a 1.5 degree Celsius rise in global temperatures over pre-industrial levels.

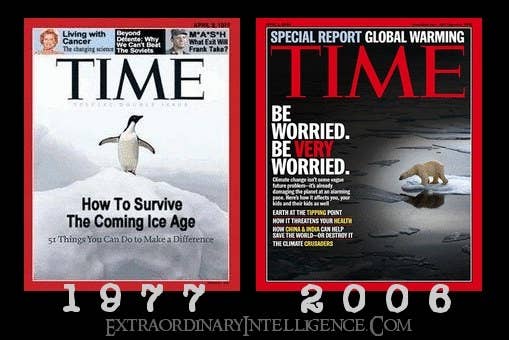

I am very much aware of that in the 1970s, some climate scientist thought we might be headed into another Ice Age. Since then the Earth has only gotten hotter, and the carbon dioxide levels have only gone up. So while the climates consensus was not 100% settled in the seventies, at this point there's no doubt, from a scientific point of view; human activity drives the observed rise in both CO2 levels and global temperatures.

|

| In a less than shocking turn of events, it turns out one of these magazine covers is fake... There was scientific debate about global cooling vs warming, so the kept records, made observations, tested hypothesizes, and came to the conclusion that cooling wasn't the problem. With science. Hooray. The system worked. |

Importantly for the topic of the next hundred years, the question is not whether the climate is changing, but to what degree. And yes that was a intentional pun. Dad jokes aside, the observed rise in temperatures are right in line with literally dozens of different models. It's almost like the science is sound. Anyway, it begs the question: What if the impacts of climate change are not reserved for the distant future?

I feel like I need to clarify a semantic point; when I say severe impacts, I’m referring to the 1 in 1000 years floods that seem to be happening every decade now, or the 1 in 1000 year droughts, or the fact that the two biggest reservoirs on the Colorado River are at only 33% capacity (and that's not normal), or the fact that Greenland is seeing rain rainfall later every year. These last two specific instances are just a smattering of the warning lights the climate is displaying for us on the metaphorical dashboard. And for the last year, average temperatures around the globe have been 1.5 degree hotter than pre-industrial temps, with no respite. This suggests that we’ve hit a new normal.

|

| Twenty years of less rain and snow looks like this.... |

I acknowledge the caveat that ‘in recorded history’ is a very limited period of time, going reliably back only to the late 1800s. Past temperature records are difficult to compile in no small part, due to a lack of thermometers and dedicated climate scientists back then. Proxy methods used to make educated guesses about the temperature of the climate are adequate, but they are not completely precise. Unlike open heart surgery, where precision is, I’m told, very important, ‘close enough’ works for the educated guessing about past temperatures. The fact that we’ve pushed our climate to high temperatures not seen since the end of the last ice age, should not console anyone.

Speaking of the end of the last ice age, about 11,500 years ago, the fact that the planet is as hot today as it was then shouldn't be a problem, right? Right? Well, not exactly.If you're interested in a deeper read about how heating after the last Ice Age influenced the rise of agriculture, I recommend The Long Summer by Brian Fagan. As you probably know, Agriculture emerged around the same time as the end of the Ice Age with wheat and barley cultivation, between the Tigers and Euphrates rivers in the Middle East, rice cultivation in southern China, and maize (corn) cultivation began about 3,500 years after that, around 8,000 years ago. While there’s quite a bit of academic debate about the how and why of the domestication of tasty plants but people, this process took hundreds of years in the case of wheat, and likely two thousand years for corn. And all this took place during a period of relative climatic stability.

This will matter a great deal going forward. To pick just one example, the NIH found that as global temperatures rise by 1, 2, and 3 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, wheat crop yields will decrease by 8%, 18% and 28% respectively, based on a study of wheat cultivars in South Africa. So simplify the research, when the temperature rises above 30 Celsius for more than 24 hours, it puts stress on the plants, which drives down yields. At night, most agricultural cultivars need temperatures to drop below 75 to grow.

Of course this is not true for tropical cultivars, but for cereals like corn, wheat and barley it is true. It's also worth noting that potatoes were originally cultivated high in the Andes mountain where they were more likely to encounter frost during the growth cycle then they were 90° day. Also thank you to the people of the southern Andes for cultivating tomatoes and potatoes they're both delicious. Why does this matter? It matters a great deal when you consider that the average human needs an average of about 2000 calories a day to survive, and most crops do not deliver the caloric content of cereal grains and potatoes.

As the hot weather of the tropics moves north into temperate zones, cereal and potato cultivation will have to move north. The lone exception is rice, which is calorie-dense but not particularly nutritious, unless it has been artificially enriched. On the other hand, one could theoretically live off potatoes alone for quite a while. Obviously, people don't live on a single crop. Human beings have always supplemented their diets with fruits vegetables, by products from animals, and yes, the animals themselves. For the purposes of our future scenario, we need to acknowledge that where people can maintain settled agriculture will have to change.

Adding to the pressure of agricultural regions moving north as the climate warms, there's a second problem with humanity’s food supply. Not only are we highly dependent on a few staples cereal crops for the majority of our calories, but amongst those crops we are highly dependent on a few strains of said crops. The risk of depending on just a few varieties seems obvious, but if it isn’t, let’s take a detour to Ireland in the middle of the 19th century.

Introduced to Ireland as early as 1590, the potato had acclimated to the Emerald Isle by 1750. As cultivation began spreading out of Munster to the rest of the Island, Irish farmers grew roughly 120 different varieties. By 1800, many farmers ate potatoes twice a day, with that number moving to three meals a day by 1840. This didn’t have to become a fatal weakness in the Irish agricultural system, but the root (heh) problem, was that Irish farmers depended on just four varieties. The 1840s were an exceptionally cool and wet decade in the northern hemisphere. The potato blight, which first struck Ireland in September 1845, is largely attributed to this temporary shift in weather. The blight attacked two of the four potato varieties, wiping out between one third and one half of the potatoes in Ireland. Without going into too much tragic detail, the crop failures of the late 1840s, combined with borderline genocidal policies set in London (wheat could've been shipped across the Irish Sea to alleviate the famine but it wasn’t) likely resulted in the deaths of 1 million people, or 15% of the population. Another 1.3 million fortunate ones, if you can call them that, boarded ships and depart Ireland, mostly bound for the United States. All this loss from a population of about 8 million.

|

| It is definitely NOT supposed to look like that. Call a doctor. |

Could such a scenario happen again today? Unfortunately, I think the answer is yes. According to the UN, corn, just four agricultural crops: corn, wheat, rice and soy, provide 60% of calories consumed by people around the world. Corn alone provides about 20% of the world’s calories. Similar to the Irish of the 1800s, the world relies on a very few specific cultivars of corn, making the crop especially susceptible to some kind of climate-driven event. Even if the crop failure alone does’t wipe out a majority of the world’s calories, most people don’t starve to death. More often, opportunistic diseases kill before the body shuts down from a lack of calories.

Leaving our food supply in a precarious position, let's move on to the second base necessity in life: shelter. How will climate change make shelter less available to people? Setting aside dramatic events like hurricanes or floods driven by a more active water cycle, according to the UN, something like half the world's population lives within 50 miles of the coast. This average is slightly lower, at 40%, here in North America. Why does this matter?

Better estimates put the rate of ice sheet loss from Greenland 20% higher than previously thought. In the fifty years before 2022, Greenland lost about 107 gigatons of ice annually. In 2022, that number nearly doubled, to 198 Gt. Just so we are clear, this is a net loss, and came from glaciers on land. And this was in the context of a climate which was still fluctuating below the 1.5 degree threshold noted earlier. I’m going to make my first bold claim; the the Greenland ice sheet will go into terminal collapse circa 2040. This means that, no matter what mitigation efforts we make, oceans around the world are on their way to 6 m of sea level rise. While this process will take several hundred years, even a 15% loss over the next 100 years would result in a full meter of sea level rise.

1 m of sea level rise would effect about 13 million people in the USA alone, and impact between 20-30% of existing shorelines. This will happen at the same time that the energy and economic base of the country will be contracting, making adaptation and recolcration even more expensive that is would be today. And this estimate doesn’t even include low-lying costal cities in poorer countries which will have an even harder time adapting, cities like Havana and Port-au-Prince.

|

| Notice any patterns? |

The third main impact of climate change on North America will be both acidification, mostly on the southern Great Plains, and intensified desertification in the border region of the USA and Mexico. This includes the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua, and the United States of Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, southern Utah and Colorado, and most if not all of California. If warming trends play out as expected, along with economic decline and mass migration, in one hundred years, I doubt the region will host any large population centers. Sure, people will live on the coast, or in high desert refuges up in the mountains, but this region will not be home to the approximately 80 million people that live there today. If the Pacific monsoons hold and rain continues to fall in the higher elevations of the Rocky Mountains, it is possible that the upper Rio Grande valley and northern Utah will continue to support settled agriculture. This trend will also play out in the higher elevations of Chihuahua and Sonora, as long as the Pacific monsoon rains fall every winter, but that's an open question.

|

| 6 meters, 18 feet, sea level rise. |

|

| 1 meter, 3 feet, sea level rise. |

If ice sheet melt, crop failures and desertification are the three negative impacts of climate change, I suppose we should acknowledge the less bad impacts. As climate belts move north, people in the Great Lakes region, and the northern portion of the Atlantic seaboard will have to grow used to climatic norms that would belong along the gulf coast today. At some point in the medium term future, likely beyond the hundred year scope of this exercise, places like Erie, Pennsylvania or Madison, Wisconsin will grow palm trees, sugarcane and dates. It also means that western Canada will transform from a place where 90% of the population lives within 50 miles of the US-Canada border, into a vast grassland habitable by pastoralist and, eventually settled agriculturalists. Eastern Canada will probably experience a climate that looks something like the American south today. They'll have a long, hot probably humid summers, but will still experience killing frosts between the Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox.

I don't know how far north agriculture will be viable in the medium, term meaning between 100 to 1,000 from now. An extended growing season and heavier rainfall will lend itself to settled agriculture, The limiting factor the further north you go will be viable soils, which take a long time to build, at a minimum hundreds of years. Soils can be depleted quite rapidly by agricultural techniques unsuitable to the climate, but I would guess in a thousand years, human agriculture will extend as far north as the arctic circle, and maybe further.

So there you have it; the North American climate will be generally hotter, with some regions drying out, others getting wetter. As agriculture belts move north and up, this will trigger movements of people, as keeping one’s belly full will outweigh attachments to place and even culture. But before we can send wave of migrants in motion, next week we will look at the broader ecological impacts of human misuse of the natural world. Welcome to the empty continent.

|

| Coming to a coastline near you... |

No comments:

Post a Comment