|

| I wonder why the water is colored brown? |

This week I plan to take us from the stratospheric themes of planet-wide ecological catastrophe, to an issue that arises from time to time in human societies: wealth and income inequality. Did I mention that Dr. Ryan Mattson and I have a book in the works on the topic? We do, and it’s set to be published by Upriver Press in the Spring of 2025. It will be available through online retailers, as well as local bookstores. If you choose to pick it up, please use the latter. If you must buy online, please avoid buying from the behemoth. Jeff Bezos has enough money already. And that’s a nice segway back to the topic at hand.

When speaking of wealth and income inequality, some commentators fall into the trap of using the terms interchangeably. This is understandable for most Americans, because most Americans have almost no monetary wealth, so income inequality feels like the only measure that might matter. That said, they're not, strictly speaking, the same thing. Income is, of course, the amount of money or goods or services that a person can draw upon over a given time interval. Do you get paid weekly? Maybe that’s your benchmark for income. Yearly? I hope you can make that paycheck stretch. Wealth, on the other hand, includes both real goods, and all the various tokens and balance sheets we’ve created to keep track of resources owed to a person by the wider society. For that really is what wealth is; not so much a tally of dollars and cents, but a way to designate who in a society gets to control resource flows.

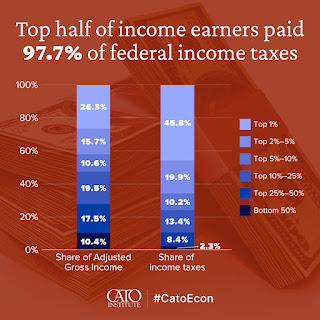

Now, there are computational tricks with which people can employ to make statistics say just about anything, with very little need for outright falsification. My favorite example is ‘adjusted gross income’ which means that, when looking at income, one must include all forms of income, not just hourly wages or salary. This includes the cost of health insurance, as well as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid benefits. This number intentionally inflates the income of lower percentile people, in a bid to show that income inequality isn’t really that bad. By using this one, simple trick, you can make it look like the bottom 50% of Americans aren't really that bad off, since they bring home almost 10% of national annual income. Take a moment to consider that; roughly 165 million Americans earn half of what the top 1%, that is, 3.3 million, earn in a year. It’s not the own the status-quo lovers think it is, especially considering that most of that health care insurance doesn’t really cover all the expenses of going to the doctor.

|

| Maybe if the bottom 50% wasn't so damn poor, they would pay more in Federal taxes. |

All that said, by any metric, income and wealth inequality in the United States is already historically high. By some measures, wealth and income inequality rivals other historical examples like pre-revolutionary France, or medieval Europe before the black death. But while historical records are spotty at best, and much of that scholarship relies on equating the yearly cut a lord took of a peasants harvest with modern wage slavery, it's worth noting that the RAND corporation, which is not exactly known as a leftist think-tank, published a paper putting the wealth transfer from the bottom 99% of Americans to the top 1 % at $50 trillion since 1978. That’s ‘trillion,’ with a T, dollars, over the last 40 years. My good friend Dr. Mattosn thinks that number is probably larger, because the impact of wealth inequality compounds over time. Thus, a dollar taken from a person’s wages in 1995 and fed to the shareholders, translates into a much larger wealth transfer today, because that extra dollar could have paid debts or been put into savings by the earner 30 years ago, rather than sitting on the balance sheets of some 1%’ers accountant. Speaking of the 1%, let’s look at one of the chief methods used by the ultra-rich to keep their wealth at the top. Let’s talk about capital gains taxes.

Just for clarity’s sake, let’s define a capital gain. When one makes money from the sale of an asset or investment, it is referred to as capital gains. Put another way, you made an investment of capital (aka money) in an asset. If you sell it at a profit, that extra money is the ‘gain.’ and the person is not taxed on the money they invested, but rather on the money made off this investment.

Put another way, if you spent fifty dollars on a rare collectible you found at a thrift store, then turned around and sold said oddity for one hundred dollars, you would have gained fifty bucks on a capital investment of fifty bucks. As long as you earn less than $47k as a single taxpayer, or $94k for a couple filing jointly, the fifty bucks you made would not be subject to taxation as a capital gain. If you made more than that, you’d technically be liable to pay a 15% tax on the profit. But your secret is safe with me.

In fiscal year 2020, Americans reported $8.4 trillion in salaries and wages to the IRS, and $1.1 trillion in capital gains. According to the Tax Policy Center, the richest 1% of Americans, made about 79% of all capital gains in 2019, and the richest 0.1% bringing in half of that $1.1 trillion in income. Put another way, the top 0.1% of American taxpayers, or about 120,000 households, made about $600 billion in capital gains in 2019. For comparison, the poorest 1/5th of American households, totaling about 66 million people, earned about $252 billion from salaries and wages in 2022, according to the US Census Bureau. Take a moment to re-read those stats. 66 million Americans brought home less than half of what the richest 330,000 made in capital gains, in just one year.

But wait, there’s more. There’s always more, isn’t there? You may have missed it up there in the description of what constitutes capital gains, but capital gains are taxed at between 15-20%, depending on how much you made (and how uncreative your accountant is). The top rate paid by those making more than $626,000 filing singly is 37%. The lesson I take away from this simple breakdown of the tax code is make money so your money can make you money, and whatever you do, don’t earn a wage or salary. Of course, how you get the money, to invest the money, to make more of it, well, proponents of our current economic system never really talk about that. At least Ray Charles did.

Let’s take a quick look at another method by which those who already have the money, make more of it: stock buybacks.

First off, what are they? Simply put, stock buybacks are a financial mechanism by which a company which issued stocks, buys them back from investors. This practice doesn’t seem so bad. After all, people buy and sell stocks all the time. Which is true, but they sell stocks to each other, rather than back to the company, and this is a key distinction.

Second, we would be remiss not to point out that these buybacks were illegal until the 1980s. The stock buyback quickly became a staple method for concentrating wealth and control in the fewest hands possible, almost entirely in the finance and investment community.

How is this done? Stock buybacks have a pernicious, two-fold effect. One - they almost always come at the expense of retail, small scale, investors, rather than at the expense of institutional investors like big money Chads. In effect, they concentrate control of companies in the hands of the investor class, who already have disproportionate control of them. But that’s not the only effect, because stock buybacks also serve to drive up stock prices. After all, the stock is in demand, but the supply is going down, so the price goes up. This means, if the institutional investors then choose to turn round and sell their stocks at a later date, they will almost certainly fetch higher prices, thus making the institutional investors richer.

Not only does this drive income and wealth inequality, but it has a third effect: money used in buybacks cannot be spent on reinvestment in the company. No hiring new workers, no higher wages and salaries, no capital investment in new equipment, no expansion of the business. This is no small point and should be reiterated. When that money leaves the company in the form of a stock buyback, the board or managers of the firm can then plausibly, if more than a little dishonestly, say that extra money to hire more staff, pay existing staff more, or invest in newer and better machinery or training programs, simply isn’t there.

|

| Don't confuse a buyback with a stock paying dividends. Uncle Moneybags certainly wouldn't. |

Take, for instance, the recent case of the General Motors stock buyback. The company announce, right after concluding a deal with the United Auto Workers union, that it would immediately buy back $6.8 billion of its common stock, with further buyback of about $4 billion planned for 2024. It’s worth noting too, that GM has not spent much money buying back stocks before 2023, with the values for previous quarters counted in the low millions of dollars. And spokespeople for the company explicitly stated the buybacks were aimed squarely at offsetting the costs of the new UAW deal, and to reassure Wall Street the company was a safe investment. Further, GM did not announce it would hold those repurchased stocks in the hopes of selling them at a later date for a higher price, but that it planned to retired the stocks. This will concentrate the holding of stocks by institutional investors and wealthy individuals.

Indeed, insiders, that is, members of its board of directors, executives and senior officers, hold nearly 7% of GM stock, with 47% held by institutional investors, and a the remaining 45% held by publicly traded companies and individual investors. These numbers alone represent a great disparity of ownership in favor of capital, but the disparity becomes even more apparent when one considers that roughly 84% of GM stocks are owned by institutions, and only 16% by the general public. To use these numbers as a rough guide, the company will fork over $9 billion to institutional investors, and about $ 1.7 billion to the general public. And wealthy individual investors dominate the category ‘general public.’ This brief examination isn’t meant to single out GM as a uniquely bad actor, but rather to illustrate the way the wealthy concentrate not just cash and assets, but control of publicly traded companies.

But the United States is not all of North America, and as noted earlier, Canada and Mexico have lower GINI coefficients than the USA, so surely that means the rest of North America will be okay. Right? As the saying went in the 19th century, when France sneezed, all of Europe caught a cold. For context, given the regularity with which France threw a revolution (1789, 1830, 1848, 1870), the impacts of those revolutions mattered a great deal to the rulers of the rest of Europe. After all, if the French are running around talking about liberty and equality and fraternity, it might encourage some of your more uppity subjects to think they need in on some of those liberal, Enlightenment values.

|

| You know you came here for the nudity! |

So I think when the United States has its revolutionary moment, and I believe the United States will, within my lifetime, the rest of North America is going to catch a cold. To stick with economic impacts alone, US-Mexico trade was valued last year at $855 billion, giver or take a few million. The value of US-Canada trade was actually a bit greater, at $905 billion last year. So even if the governments of the other two big North American countries could somehow seal off their nations from the US, the economic impacts of a trade disruption caused by a revolution or civil war or full-scale break up, would be immense for both Canada and Mexico. This outcome shouldn't come as a shock to anyone. The implosion of governmental structures and political economies in one country inevitably affect the countries around them.

Before we talk about guillotines, tumbrels and revolutionary chaos, we should at least mention what might be done to avoid the more violent outcomes linked to economic inequality. I plan to touch on that next week ***spoiler alert*** but for now, there are some political solutions economic inequality in the United States that don’t have to involve severed heads and mob violence.

|

| Tumbril, guillotine, revolutionary chaos! This painting has it all!! |

A fairly straightforward right-of-center solution to income inequality would be an enforcement of anti-trust laws. If the federal government were to get its act together and break up all of the gigantic firms that dominate American economic life, we might see a genuine trickling down of wealth to the working classes that create that wealth. I think it's worth noting that in almost all sectors of the American economy, from finance to agriculture, to manufacturing, to media a scant few firms functionally control their respective markets. The biggest, most obvious example is Amazon, which controls somewhere around 40% of U.S. e-commerce.

But there are also less obvious oligarchies or near monopolies, think of the car industry. We used to have a literally a dozen big car makers, until they were bought out by the big three, which is now functionally a big two. Or think of the banking sector in the way in which so many large banks have been bought out by each other in the wake of the 2008 .Financial crisis and the current brewing financial crisis of smaller midsize banks failing along with the commercial real estate market teetering on the brink of failure.

Or consider agribusiness. We have four or five firms, depending on which specific field of agriculture you're looking at, which control 80% of agricultural production in the United States. We could go down a whole laundry list of the ways in which the economic well-being of Americans are controlled by people that live in many cases hundreds or thousands of miles away.

But the United States did not always work like this. It has literally been in my lifetime, in the last 40 years, that economic power in corporate consolidation has moved so quickly and aggressively to put the economic reigns of the country in as few hands as possible. That only does this make markets less competitive, it also disincentivizes the ownership class from sharing any of the profits or wealth with the people who work for them because they are so distant and disconnected from their very own workforces.

There are a handful of what might be deemed centrist solutions are these typically are the neo liberal grab bag of slightly higher marginal taxes maybe a little more social spending over here or over there they don't really tackle the core of the problem but might be enough maybe to head off truly revolutionary fervor.

And then there are the left of center solutions these include things like universal basic income out now expropriation or my personal favorite solution turning ownership of private industry over to the workers that actually work in those businesses. Without going into too much detail about what each solution might look like in terms of real policy I've been told that universal basic income as viable as long as the Federal Reserve agrees to go along with it. Similarly state ownership and expropriation of large businesses and industries can be done without going for communist. Nationalizing of industries to break up large firms would be similar to the anti-trust solution mentioned earlier but might go further or have more further reaching consequences in terms of permanent downward redistribution of wealth.

As a pragmatist myself I think that and all of the above approach would be ideal from a policy perspective both Bret breaking up large businesses through anti-trust laws and turning over the ownership of those businesses to the employees of the businesses would ideally create a healthy free market well at the same time resulting in the real redistribution of wealth and ownership to the people networking those businesses. But I don't think most of you reading this came here to read about Ben Johnson's ideal policy solutions to an incredibly complex topic.

So let's get on to what this implies about the future of North America. Insured as mentioned earlier what happens in the United States will spill over in affect the other countries in North America and there's nothing either side can really do about it. While it might be tempting for Canadians to say oh we can sell our manufactured goods and oil to other countries, or perhaps for Mexico to say “OK, we will become the middle manufacturer for some other advanced economy like Japan or Western Europe,” that's simply not how I think history will play out. Due both to the geographic proximity, and to the degree that international trade has bound Mexico, Canada and the United States to each other. And when the United States experiences its revolutionary crisis the other two countries will be affected, probably to a greater extent that they anticipate.

|

| Nothing screams "FREEEEEEDOMMM!" quite like being an armed enforcer for the State. But I'm sure they'll respect your civil liberties... |

There are a number of events, driven by economic inequality, which could cascade into outright revolution here in the US. The most obvious would be some sort of financial crisis, likely driven by defaults as fewer and fewer people and businesses can service their debts as ever more money gets hoovered up by the top income bracket. This would look a lot like the 2008 financial crisis, which quickly transforms into wider demands, not just that policy makers address the immediate crises, but the underlying causes. There are other scenarios that could result in a revolutionary moment: some proxy war spirals out of control and disrupts global shipping could cause a finance-heavy economy like the US to experience a sharp economic contraction, or we could get a self-own. I’ve seen reliable reports that the incoming US administration is seriously considering repealing laws requiring employers to pay a minimum wage and/or overtime pay. I like to imagine that would bring a large number of people out in the streets demanding change. There are any number of ways an economically unequal society reaches a breaking point.

Cynics might argue that regimes ' buy’ civil order through bread and circuses. In modern parlance, we might say that the ruling class in the United States keeps people pacified with reality TV and microwave dinners. But what underlying cause can push a population to reject reality TV and microwave dinners, and out onto the streets in protest, which can lead to violence, which can lead to regime change?

|

| Maybe we can finally put all these lifted pickups to good use? |

Economist Debraj Ray of NYU, proposes two measures to consider: fractionalization and polarization. Fractionalization in this case means the degree to which any given society contains various groups which may be quite different and diverse. In contrast, a polarized society would have two main groups, each quite similar internally, but quite different from each other. In Ray’s studies, fractionalization, whether along ethnic or religious lines, showed no correlation with civil conflict. On the other hand, high polarization of society did show a significant correlation with civil conflict. That is to say that societies containing various groups: culture, religion, or ethnicity, aren’t predetermined to descend into violent conflict. However, those that are separated by class, and in particular a highly unequal class divide, tend to be associated with violent conflict.

This notion may seem contradicted by anecdotal evidence. Anyone even vaguely aware of the long, sorry history of ethnic violence, could easily name half a dozen conflicts in which the two, or more, sides claimed either a religious or ethnic, or other, motivations for collective violence against another group. The claim Ray makes is no direct link, statistically speaking, of ethnic or religious fractionalization, on the likelihood of the occurrence of civil conflict. He does not say it might not indirectly affect civil conflict.

Instead, Ray points to per-capita income as measured in GDP US dollars, as strongly significant both statistically and substantively. This doesn’t mean every poor country is always primed to go off like a powder keg after a book of lit matches gets tossed at it. If everyone is poor and close to the GDP per capita line, they are economically engaged, and largely egalitarian. Ray points out that polarization means that as income clusters are more and more in the hands of one group, it polarizes the ‘other’ group in society against them. People that fall further and further from the GDP per capita line are more marginalized and have less to lose. And as a larger population falls further and further from the GDP per capita engagement line, their fight becomes more existential and desperate.

Ray, drawing on other’s research, takes care to point out that this shouldn’t be seen as the only factor. Another factor that matters is how dispersed economic and political power are within a system. In a system which is more dispersed, group loyalties remain localized, and demands of one group may be met or placated, without injuring the interests of other groups. A cynic might think of this as the technique of ‘divide and conquer’, but that somewhat misses the point. Whether they intended it or not, the framers of the US constitution built such a system, and in his own writings, Ray describes such a system as federalism.

In the not-so-distant past, laws and economic arraignments could vary quite broadly from state to state. For an example, consider the impact of laws allowing commercial banking across state lines. Previous to the 1980s, banks were generally confined to a state or region. This “artificial” restriction balanced the potential increasing returns inherent in markets like lending and deposit services, and provided for smaller banks and credit unions to get a start and compete with their regional, older siblings. After the deregulation of the 1980s, banks were allowed to compete across state lines and take advantage of the increasing returns to scale; that they could decrease their average costs while increasing the quantity of services they provided. I'm sure you'll be shocked to find out that Federal Reserve research has found that bank consolidation is not the result of 'natural' market forces, nor does in improve outcomes for customers...

|

| Pictured: the US banking regulatory system. |

Ray contrasted federalism with a centrally focused system. Not only does such a system vest most political power in the hands of a central government, such societies can be quite susceptible to forming polarized groupings; those who hold and/or benefit from economic power, and the majority who do not. These polarized societies might possess fewer cleavages compared to a federalized society, but the cleavages that do exist run through the whole of society, and thus feel more important. Therefore, when conflict occurs, the central authorities will find it hard to placate one group without antagonizing the other.

Ray also points out the phenomenon of ‘local compression’ vs ‘global compression’ as another key driver of civil conflict. In this case, the terms local and global do not refer to physical geography, so much as they refer to the distribution of income and/or wealth. Where people experience local compression in an economic system, populations cluster along specific segments of the income/wealth scale. In practical terms, this might mean a lot of poor people, few people in the middle income brackets, and a second, smaller cluster in the top brackets.

In the meantime, let's spin out a quick scenario for how it might happen and what the implications would be for the other countries of North America. In the interest of limiting the scope of the scenario I will assume that sometime next year, maybe the year after, widespread defaults in the commercial real estate market lead to a generalized banking crisis. The specifics of who defaults and who gets bailed out aren’t per se important, what's important is the optics of yet another financial crisis in which the rich get bailed out and we, ‘the poors,’ get to fend for ourselves. But let's say this time the anger of the American people can't be mollified by another general election.

So mobs take to the street, demanding the reversal of whatever policies are seen as causing the most pain. As police crackdowns on protests routinely backfire, and the political establishment seems more and more tone deaf to the moment this revolutionary moment, lines get drawn in peoples’ hearts and minds. Equally important would be the loss in value of the dollar as the crisis drags on. As the dollar loses its value, budget crunches hit municipal police departments; the police officers may no longer feel like it's worth it to put on riot gear and beat down their fellow citizens in defense of laws they might hate just as much as the protestors.

|

| I'm sure this won't end badly... |

This collapse of economic viability in the United States would result in a shut down of supply chains in Mexico, as well as energy exports from Canada to the United States. This results in people in both countries also either losing their jobs, seeing their wages cut back, or seeing a collapse in their purchasing power. How this plays out would depend on internal factors. In Canada we might see a situation in which the western provinces demand control over how much tax revenue gets sent to Ottowa, rather than kept local to deal with the economic downturn. In Mexico, the loss of manufacturing income combined, with a government that is of dubious legitimacy and constantly embroiled in armed conflict with drug exporting cartels, might lead people into the streets to call for a dissolution of the country along regional lines. Or perhaps the forces of revolution would not be centrifugal in either case.

Snap elections in Canada might bring to power a coalition which seeks the creation of even more central authority, in order to weather the crisis. In Mexico, it could lead to the instillation of a strongman who follows a method of dealing with street gangs similar to the President of El Salvador.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. I will explore the interplay of all those forces in the full scenario; so for will call it a day. Next week, we will move on to our sixth, and most unpredictable factor: the national politics of the United States..

No comments:

Post a Comment